About mud paintings

Soil is alive.

After the invention of the microscope and just as we were discovering bacteria, a 19th century Ukrainian biologist named Sergei Winogradsky put soil in a glass column on the windowsill near his desk. He was determined to understand what was going on inside the soil. Over time a red splotch formed in the brown soil column; he put his pipette down into the red spot and looked under the microscope – the particles moved!

Bacteria paint.

Using Winogradsky’s technique, I make living color field paintings with microbes that photosynthesize pigment in unique soil samples. While individually invisible to the human eye, bacteria growing in the presence of light amass blocks of color as defined by chemical and physical conditions in each sample. As one species exhausts its preferred resources and dies out, another species thrives on the waste products of its predecessor. Transition in color indicates ecological succession of microfauna metabolizing a livelihood within a finite ecosystem.

Winogradsky Rothko, 2004

My first mud painting (used mud from Beebe Lake, a swimming hole in Ithaca, NY) was named after the soil scientist Sergei Winogradky and the colorfield artist Mark Rothko (known for horizontal bands of color). This pairing was chosen because the Winogradsky column sets up horizontal ecozones, with a sulfur rich anaerobic bottom and a sulfur poor aerobic top, resulting in a gradient that selects for different bacteria; the different bacteria create different colors in different horizontal zones, not unlike a Rothko painting.

How a Winogradsky Column works.

note, this pdf was downloaded from biointeractives.org

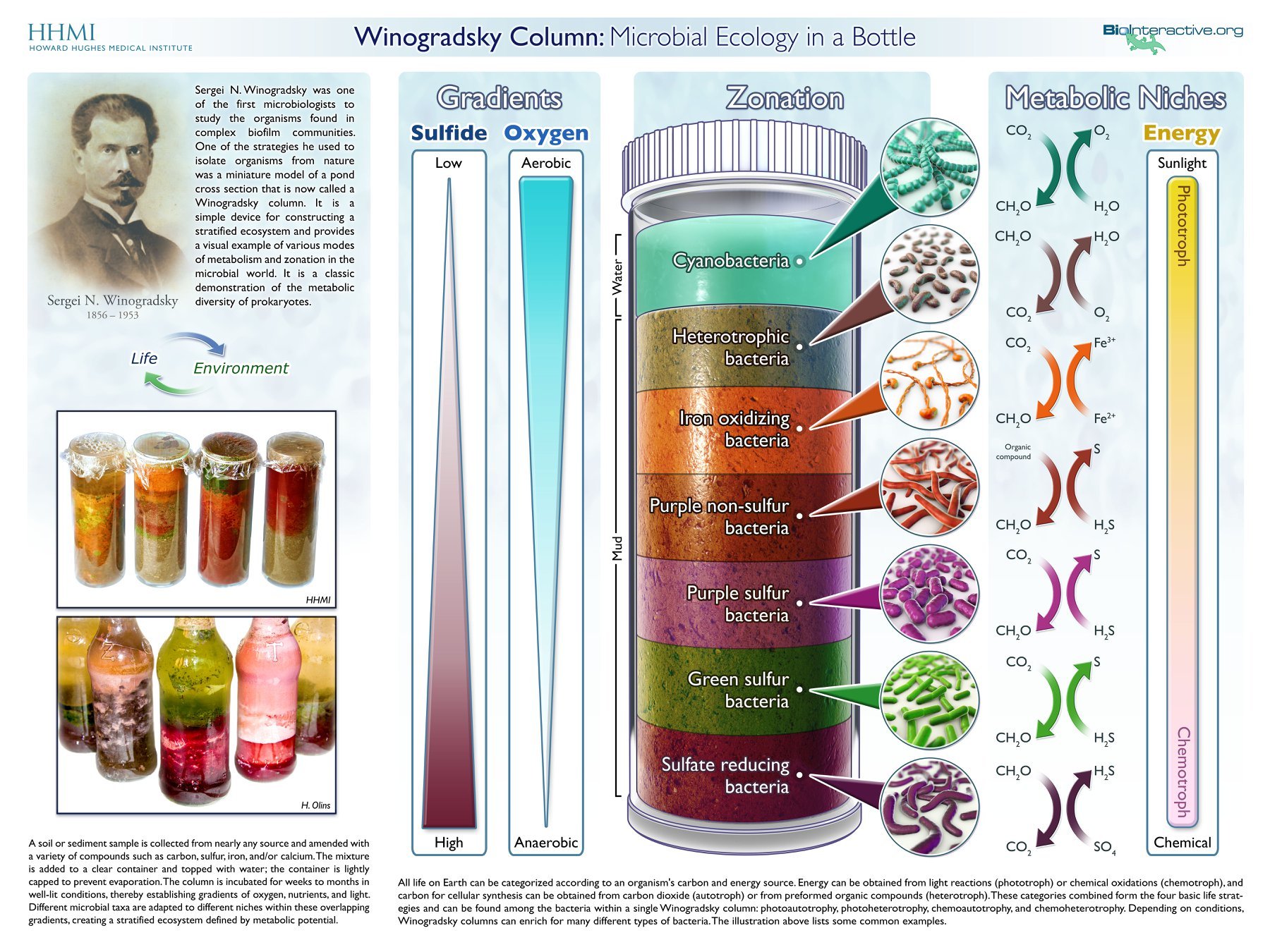

Two inverse gradients (sulfide and oxygen) set up a range of ecosystems (high oxygen low sulfide at the top, some sulfur some oxygen in the middle, high sulfide low oxygen at the bottom) selecting for different bacteria that make their livelihoods from the different metabolic niches.

Make Your Own!

To make your own mud painting, Just do the following!

Find a clear soda bottle

Collect your mud (shovel, bucket, and an eye for anything that is different from anything else and scoop!)

Get some chalk (it acts as a pH buffer), some eggs (the more eggs the stinkier, so beware), and some shredded newspaper (it's like microbial potato chips - fast energy).

Mix it all together, cover the soda bottle opening w seranwrap and an elastic band, and place it in your window!

Daydream like Winogradsky and conceive of the "Cycle of Life".

Or go to these resources for methods.

Soil Science: Make a Winogradsky Column, Scientific American 2013

YouTube by NASA scientist Dr. Dodson

Writings

Winogradsky Rothko: Bacterial Ecosystem as Pastoral Landscape

Journal of Visual Culture. 2008;7(3):309-334. doi:10.1177/1470412908096339

Made in the dimensions of a Mark Rothko painting, a steel and glass frame was filled with mud and water. By applying a microbiology technique developed by a 19th-century soil scientist, Sergei Winogradsky, pigmented bacteria that existed in the mud and water composed a landscape. As bacteria colonize their optimal zones, they change their environments by depleting their resources and releasing by-products. As a bacterial species reaches its carrying capacity, the environment no longer hospitable to the original colonizer may now be the optimal environment for a potential successor to that zone resulting in an evolving color-field of living pigments. The appearance/disappearance of color indicates both procurement and loss of finite material resources; the agents that act out upon the landscape and synthesize change become acted upon by their consequentially changed world. For this article, the ecological industry of the figure and field of Winogradsky Rothko serves as a point of departure for thinking toward a notion of ecological rationality.

Landfill dominion: The economy of a man-made neo-paradise.

Technoetic Arts. 2018;16(3):335-343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1386/tear.16.3.335_1

ABSTRACT: Herman Daly once identified the absurdity of shipping Danish cookies to the United States; if efficiency were in fact ‘economic’, one might just e-mail the recipe, save the fuel, reduce the greenhouse gases and still enjoy the cookie. This argument playfully illustrates that resources are scarce, ideas are Inherently Not Scarce (INS) and current financial systems are inefficient and not ‘economical’. The unprecedented industry of 7.5 billion people is now concerned about the resulting scarcity and pollution of the finite resource base. Until humanity shares inherently-not-scarce ideas for effectively managing what is in a steady state, scarcity and pollution will be a constant source of crisis on the landscape. Since 2004, I have made transforming colour field paintings with mud taken from the most pristine to the most toxic landscapes of northeast United States of America (NE USA). Although difficult to see individually, microbes existing within mud photosynthesize pigments. As a species grows from individual to colony, it becomes visible as pointillist pigments amass horizontal blocks of transient colour. As these bacteria express themselves (i.e., live: consume, reproduce, deplete resources, release wastes), they exhaust their habitat and create an altered landscape suitable to a successor. Like us, bacteria are bound by the law of conservation of mass; they constantly select and reject resources from the finite landscape. The resulting processes of growth and decay are intimately linked inversions resulting in beautiful transforming colourfields. As evidenced by my vibrant and literal portraits made from mud, these simple, highly adaptable, single-cell organisms craft a unique, colourful and synthetic existence. As a model system, they exhibit a viable steady state of infinite expression in a finite landscape where life and landscape is an intimate, malleable and reciprocal whole. Here I discuss the beauty of our landfill paradises, made evident by mud taken at two different kinds of landfilled ecosystems in New York City.

Material Empathy in an Indivisible Landscape:Colorful Bacteria Colonize the Underbelly of NYC's Most Polluted Waterways

Proceedings of Taboo, Transgression, & Transcendence in Art & Science. 2016:435-445. https://avarts.ionio.gr/ttt/2016/en/proceedings/

ABSTRACT: In Robert Smithson's 1973 Artforum article "Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape", he suggested that the art of remediating could be termed "mud extraction sculpture" where "A consciousness of mud and the realms of sedimentation is necessary in order to understand the landscape as it exists." Extraction engages a process of selection and rejection. In the pursuit of selecting a desired form (positive), an offcast waste product (negative) is also formed. These “wastings” from “production”– often recognized for having adverse impacts on the ecosystem – create new landscapes. In the United States, the worst of these “new” landscapes are designated Superfund Sites (aka Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 [CERCLA]), requiring national, state, and polluting industries to pool funds to remediate highly contaminated sites. To see what was living in New York City’s three Superfund sites, I fabricated steel and glass frames to hold mud and water from each: Hudson River (Polychlorinated biphenyls, PCBs), Gowanus Canal (mire of industrial wastes), and Newtown Creek (chronic oil contamination larger than the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill). As evidenced by these vibrant and literal portraits made from the mud of three Superfund sites, our “wastescapes” still afford simple, highly adaptable, single-cell organisms a viable landscape to craft a unique, colorful, and synthetic existence. Of course, these human transformed habitats are not amenable to all life but the industry of microbial metabolism continues. Life & landscape is an intimate, malleable, and reciprocal whole.